On Tuesday nights in a converted warehouse in South London, the tatami sounds like bubble wrap being stomped by ghosts. A dozen adults—parents, engineers, accountants—hit the mat in a rhythm that’s half ritual, half rebellion against sedentary life. What’s always striking is how steady some of them seem. One woman jokes mid-warmup that her inbox has “gone nuclear,” yet she moves as if her nervous system didn’t get the memo.

Why do some judoka appear unshakeable—even when life outside the dojo is anything but? And why do so many report feeling mentally clearer, calmer, and more resilient after just a few weeks back on the mat?

We often talk about judo as a physical art: kuzushi, timing, grip fighting, conditioning. But quietly pulsing underneath every throw, fall, and frustrated reset is a psychological engine—one that modern research is only now beginning to quantify.

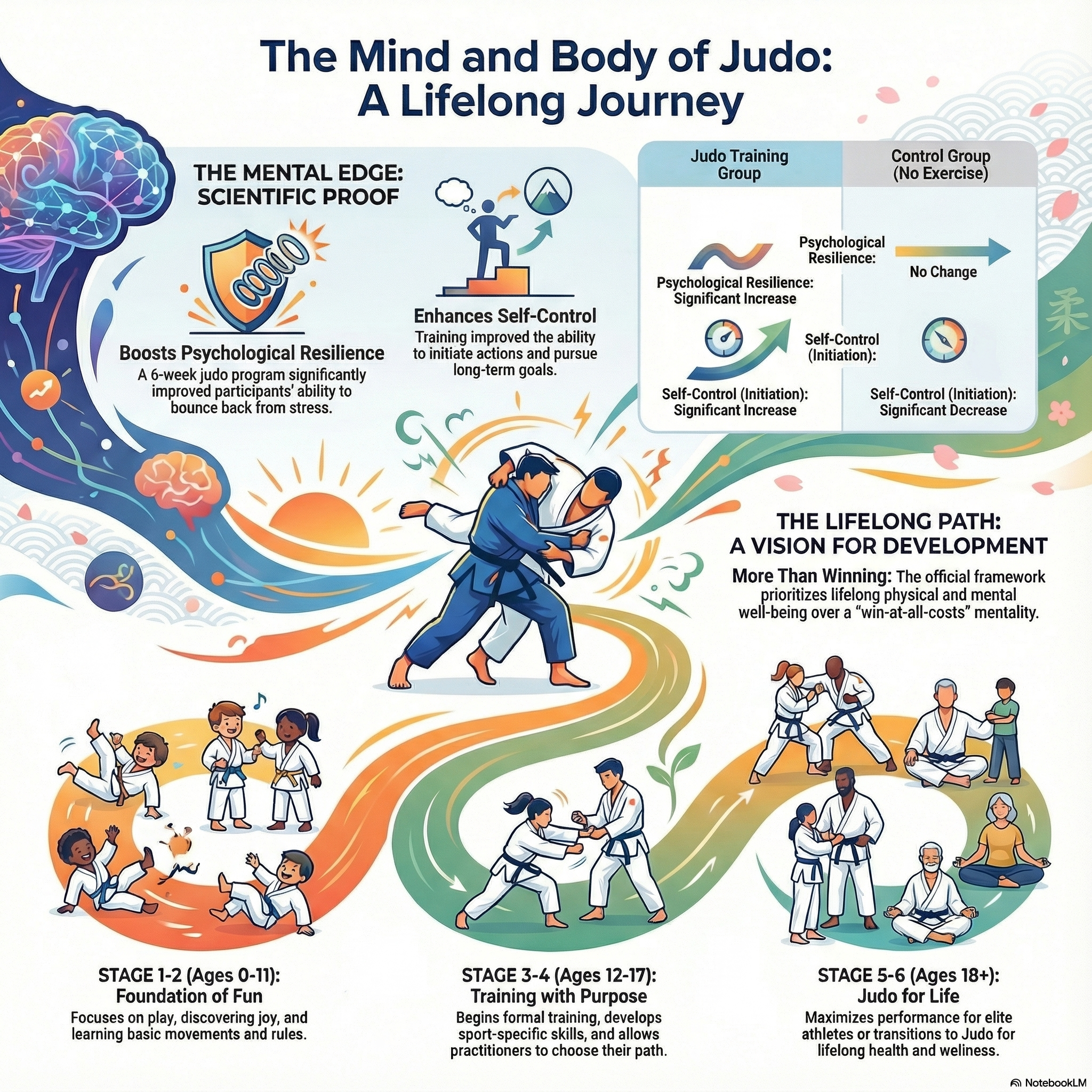

A recent synthesis of findings from Frontiers in Psychology and the All Japan Judo Federation’s Long-Term Development Guidelines reveals something many of us have felt intuitively: judo doesn’t just shape the body. It reshapes the mind—quickly, measurably, and in ways that intersect with the wider cultural moment of burnout, midlife reinvention, and the search for meaning in movement.

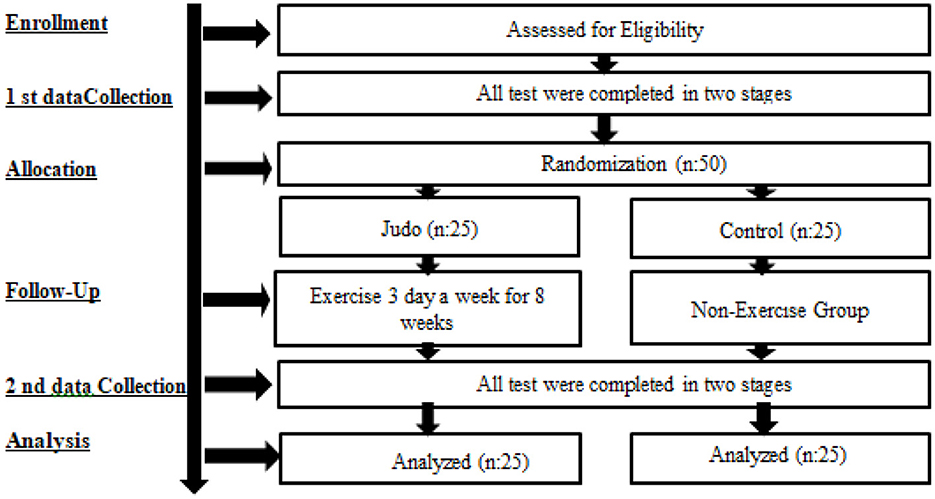

In this NotebookLM podcast, we speak judo and its about beneficial effects on mental well-being and its role in structured, long-term human development. A 2025 research article details an experimental study demonstrating that a six-week judo training programme led to significant improvements in psychological resilience and self-control in healthy, sedentary male subjects. Complementing this, the All Japan Judo Federation’s Long-Term Development Guidelines presents a comprehensive strategy to revitalise participation, addressing challenges such as early specialisation and coaching quality.

Resilience on the Tatami: More Than Just Grit

When Mehmet, a 44-year-old brown belt and father of three, returned to the dojo after a year of relentless work stress, he expected his lungs to revolt. What caught him off guard was something subtler: on the train home one night, he noticed he wasn’t clenching his jaw. The argument he’d had with his boss earlier that week felt like it belonged to another person entirely. This isn’t anecdotal magic.

A six-week beginner judo programme produced a “substantial and robust impact on psychological resilience” in a group of sedentary university students.

Why so fast?

Because judo offers something most adults rarely encounter in everyday life: structured adversity. Not the chaotic kind that drains you, but the rhythmic, predictable kind the nervous system can metabolise. Every class is a lab for stress inoculation:

- being pinned and solving the problem instead of panicking

- failing a throw and resetting instantly

- absorbing impact through ukemi until falling feels ordinary

- navigating fatigue while staying technical

Each repetition teaches the brain: stress is information, not danger.

Resilience in judo isn’t a heroic trait. It’s something you absorb—quietly, like sweat into the seams of a well-worn judogi.

The Discipline Loop: Starting When You Don’t Want To

One of the most striking findings from the Frontiers study was the improvement in self-control—specifically initiation. Not inhibition (holding back), but the ability to start meaningful actions even when short-term comfort pulls the other way.

For adults, this lands like a revelation. Modern life is an endless negotiation with procrastination—gym memberships that become donations, unread books stacking like geological layers, good intentions buried under digital noise.

But judo creates hundreds of micro-initiations:

- Step onto the mat even when your knees ache.

- Start a new drill even after being thrown five times in a row.

- Attack again after your partner shuts down your first three attempts.

Judo builds the habit of beginning anyway.

Interestingly, the study found little change in inhibitory control. That tracks. Judo isn’t about not acting—it’s about acting with precision. Self-control here isn’t a brake pedal; it’s an ignition system.

This makes judo uniquely powerful for adults stuck in cycles of overwhelm, burnout, or decision fatigue. It transforms “I don’t feel like it” into “I’ll begin, and the feeling will follow.”

Feeling Your Way Through Combat: Emotional Expression in Motion

The research noted modest improvements in emotional expression, but this subtlety hides something more interesting.

Judo doesn’t teach catharsis.

It teaches integration.

Take Anya, a 38-year-old project manager who arrived at her first session with the emotional range of a well-composed email. Six months later, she can channel frustration into snap-down intensity, disappointment into tactical adjustment, and determination into the kind of newaza pressure that feels like a weighted blanket with opinions.

Judo gives adults—especially those conditioned to remain externally composed—a controlled space to connect feeling to action.

Up to this point, judo sounds like a miracle drug: resilience, discipline, emotional clarity. But here’s the uncomfortable truth—judo also has a reputation for injury, attrition, and competitive pressure that pushes many adults out before these benefits fully land.

Jigoro Kano’s Forgotten Equation

The All Japan Judo Federation’s (AJJF) Long-Term Development Guidelines highlight a shift away from the narrow, medal-centric model and back toward Kano’s founding triad:

Physical Education + Competition + Moral Cultivation.

Kano didn’t design judo to be a combat sport first. He designed it as a system for human development—shockingly aligned with today’s concepts of physical literacy, lifelong learning, and psychological well-being.

For middle-aged practitioners, this reframing is liberating. It means:

- you’re not “too late”

- your best judo might be mental, not physical

- your practice doesn’t need to orbit tournament success

In other words, even if your competition days are long behind you, your growth curve in judo is not.

A Pathway Through Life: Judo for Every Age

The AJJF outlines six developmental stages culminating in judo as a lifelong practice oriented toward:

- fall prevention

- joint health

- social connection

- cognitive sharpness

- stress regulation

Further Reading: All Japan Judo Federation (2024) Long-Term Development Guidelines.

Picture a 60-year-old who trains twice a week not to compete but to stay mobile, stay balanced, stay human. This isn’t utopian—it’s essential, given judo’s documented population decline.

And the psychological benefits?

They don’t fade with age. If anything, they compound.

In a culture obsessed with optimisation and self-tracking, judo offers something more analog, more grounded, and arguably more necessary: a ritualised encounter with challenge that keeps the mind young by keeping the body honest.

Takeaways for the Tatami

• Judo builds resilience quickly—even in beginners—because it offers structured, repeatable encounters with manageable stress.

• Self-control improves through action, not avoidance; judo strengthens your ability to initiate meaningful effort.

• Emotional expression grows subtly, helping practitioners connect movement, intention, and feeling.

• Kano’s original vision aligns with modern psychology: judo develops the whole person across physical, mental, and moral dimensions.

• Judo is uniquely positioned as a lifelong practice—supporting mental health, physical literacy, and community well-being into older age.

Final Thought

In a world engineered to eliminate friction, judo offers a countercultural gift: a place where struggle is expected, where progress takes the shape of a fall, and where refinement happens slowly, one grip, one reset, one quiet breath at a time.

How might your practice change if you saw every session not as exercise, but as an investment in the person you’re still becoming?

Quiz: According to the Frontiers study discussed in the post, which psychological attribute showed the strongest improvement after six weeks of beginner-level judo training?

A) Emotional expression

B) Inhibitory self-control

C) Psychological resilience

D) Stress tolerance

Answer

Correct Answer: C) Psychological resilience

Explanation: The study reported a “substantial and robust impact” on psychological resilience (effect size 1.047), making it the strongest improvement among the measured psychological variables in beginners.

(1) Köroǧlu, M., Yılmaz, C., Tan, Ç., Çelikel, B.E., Budak, C., Kavuran, K., Susuz, Y.E., Barut, Y., Ceylan, T., Soyer, F., Sezer, S.Y. and Şahin, F.N. (2025) 'Judo exercises increase emotional expression, self-control, and psychological resilience', Frontiers in Psychology, 16, p. 1632095. Available at: doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1632095.

(2) All Japan Judo Federation (2024) Long-Term Development Guidelines

Member discussion: