Can You Think Your Way to Victory?

Your opponent bows. The referee calls hajime. And something goes wrong before anything physical happens.

Your grip sequence vanishes. Your feet feel heavy, like they’re sinking into the tatami. The noise of the hall dulls. You know what you should do — but the moment arrives faster than your body can organise itself. By the time you recognise the hesitation, you’re already airborne. Lights. Ceiling tiles. Impact.

Back in the chair, everyone will explain what happened. Poor grips. Bad timing. Lack of commitment. No one will ask what your pulse was doing when the referee spoke.

In judo, we treat moments like this as technical failures. The growing body of sport psychology research suggests something more uncomfortable: the throw often happens after the mind slips — not before.

In this NotebookLM podcast, we explore the crucial role of psychological factors in judo performance, highlighting their importance alongside physical prowess. We discuss how mental preparation, encompassing areas like motivation, self-belief, and stress management, can be the deciding factor in high-level competition.

⸻

It’s Not Just Physical: The Mental Side of Judo

Mark Lonsdale, a leading figure in judo psychology, puts it bluntly:

“In any sport, including judo, the mental aspects of competition are every bit as important as the physical aspects, but often neglected.”

The data backs him up. A comprehensive review by Rossi et al. (2022) found consistent psychological markers separating winners from losers. High performers exhibit less anxiety, more motivation, and stronger self-confidence. These aren’t personality traits—they’re trainable skills.

So why do we still treat mental preparation like an afterthought?

⸻

The Comforting Lie Judo Tells Itself

Judo has long believed that mental toughness emerges naturally from physical hardship. More randori. Harder training. Tougher weight cuts. Pressure, repeated often enough, is assumed to forge composure.

It’s a reassuring idea — and a deeply flawed one.

If exposure alone built psychological control, every exhausted judoka would be unshakeable under pressure. Instead, many collapse at the very moment when calm decision-making matters most.

This belief persists not because it works, but because it’s convenient. Calling mental training “soft” excuses coaches from learning a skill they were never taught.

⸻

Mood, Motivation, and the Inner Judo Landscape

Elite judoka don’t just have good throws — they have managed inner states. Negative emotions like anger, tension, and confusion spike when performance drops. Meanwhile, motivated athletes with high vigor tend to dominate.

If suffering automatically built mental toughness, weight-cut judoka would be unshakeable. The opposite is usually true. Rapid weight loss increases fatigue and irritability while draining that vital sense of go.

Motivation and mental toughness go hand in hand. Lonsdale defines mentally tough athletes as those who stay composed, confident, and laser-focused under pressure. It isn’t magic. It’s discipline — learned, reinforced, and trained.

⸻

The Pivot: Where Judo’s Assumption Breaks

For years, judo assumed mental toughness was forged by exposure. The problem isn’t that this belief is old-fashioned — it’s that it’s demonstrably wrong.

Pressure doesn’t teach regulation. It reveals whether regulation has already been trained.

Repeated stress without coping tools doesn’t build resilience; it often amplifies anxiety, avoidance, or emotional shutdown. In other words, judo’s traditional solution to pressure is frequently the thing that makes pressure worse

⸻

Finding the Sweet Spot: The Optimal Stress Zone

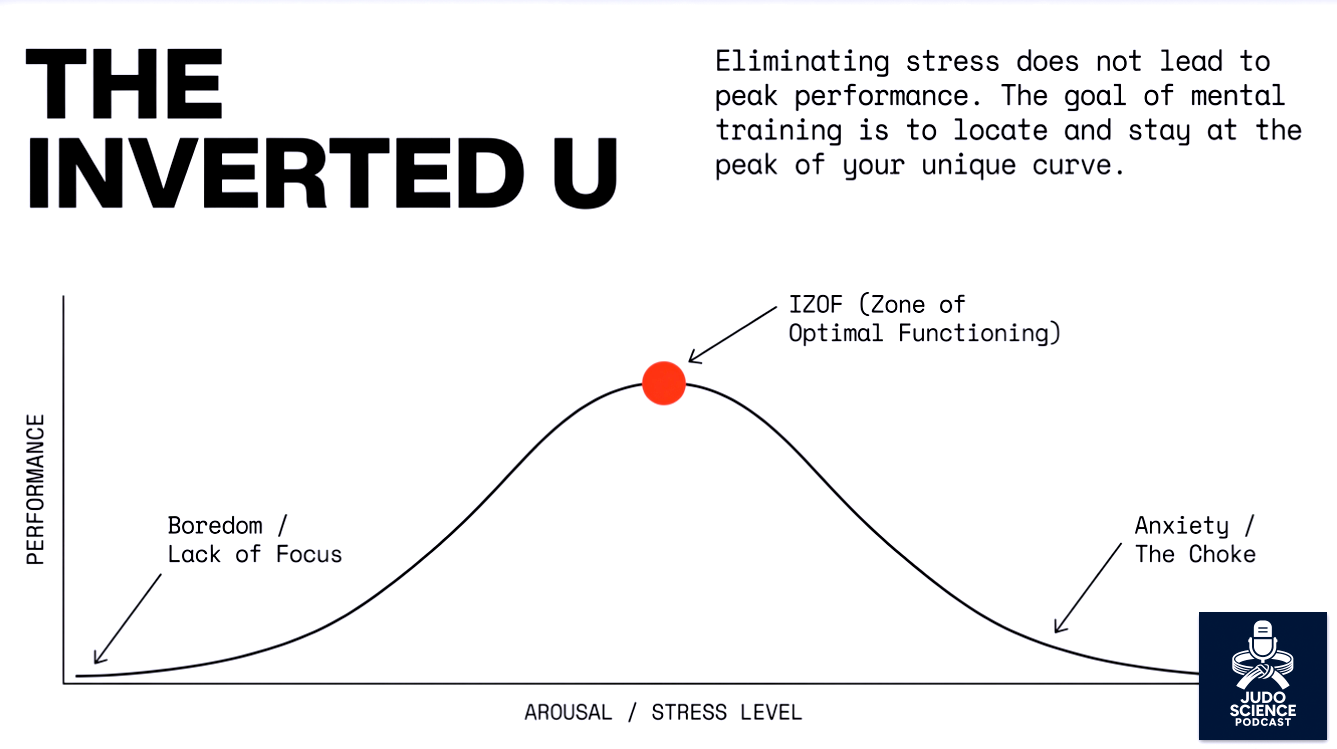

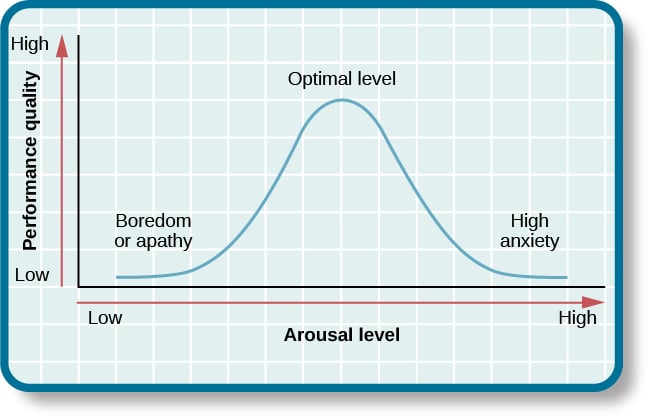

Too much stress tanks performance. Too little, and you’re flat. The Yerkes–Dodson law maps this relationship as a bell curve, with a narrow “zone of optimal stress” in the middle.

Crucially, this zone is individual. Some athletes thrive on intensity; others unravel. Coaches who understand this can help judoka find their ideal pre-match state.

The problem is that most judoka are handed the dial and told to “figure it out” under competition lights. Stress isn’t the enemy — it’s a control variable. The goal isn’t calm. It’s regulation. Crank it when you need fire; cool it when you need flow.

⸻

Emotional Control: The Hidden Technique

Think of emotion regulation as a judo technique for the mind. It’s the ability to monitor and manage emotional reactions in real time.

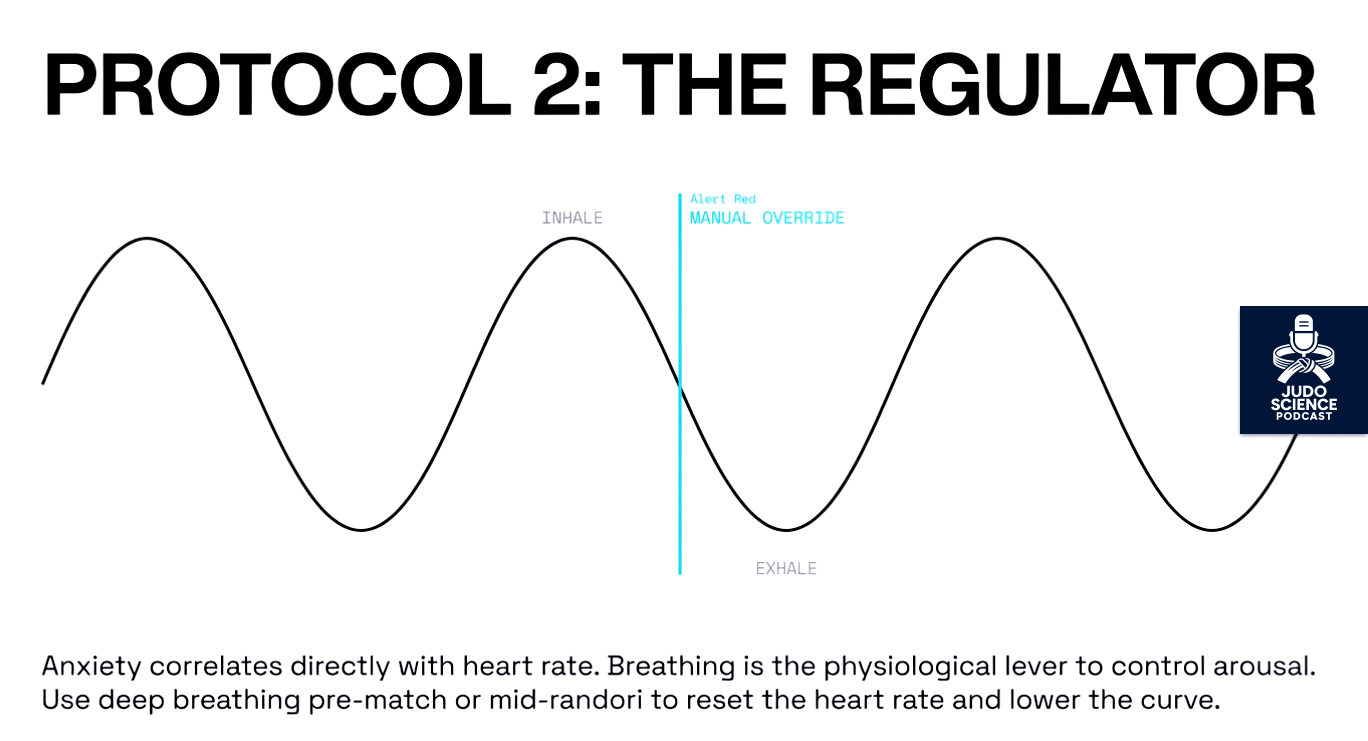

Top judoka use both problem-focused coping (tactical adjustments) and emotion-focused coping (reframing mistakes, regulating arousal). Simple tools matter. Deep breathing. Visualisation. Attention control.

The best athletes train these skills like uchikomi. They simulate high-stress environments and practise thinking clearly while fatigued. One method: solving simple maths problems immediately after intense randori. It sounds odd — and it works.

⸻

Tasha, a junior national champion, used to vomit before matches. Her throws were flawless in training but collapsed under pressure. After working with a sports psychologist, she began visualising matches while doing burpees — recreating competitive fatigue and stress.

Six months later, her win rate doubled.

To see these concepts in action, check out this in-depth conversation with Dr. Derek Mueller on sport psychology and competitive pressure. He explores how mindset training is integrated into elite judo and BJJ programs.

⸻

Coaches: More Than Just Technicians

A coach who only teaches technique misses half the picture. Great coaches understand emotional rhythms as well as biomechanics. They help judoka set meaningful goals, take ownership of training, and interpret wins and losses constructively.

That includes resisting the self-serving bias that credits success to skill and blames failure on bad luck. Growth happens when athletes accept that effort, preparation, and mindset drive outcomes.

Some purists still scoff. ‘Judo is about feel, not feelings,’ one coach told me. But the numbers—and the medals—say otherwise.

For a hands-on guide, the article “Mental Skills for Athletes” from JudoAdvisor lays out actionable strategies for coaches and athletes alike—including mental routines, visualization drills, and stress inoculation practices.

⸻

Takeaways for the Tatami

- Mental training is as essential as physical training

- Mood states influence performance more than we admit

- The right level of stress boosts performance; too much derails it

- Emotion regulation and coping strategies can be taught and trained

- Coaches must support athletes’ psychological as well as physical development

⸻

Final Thought

That opening judoka doesn’t need a new throw. They need to recognise the moment before their thinking collapses — the tightening chest, the shallow breath, the narrowing attention — and intervene while they still have agency.

That isn’t softness. It’s skill. Judo has always prized adaptability: yielding to force, adjusting under pressure, responding instead of resisting. Yet when it comes to the mind, the sport still clings to the belief that exposure alone will do the work — that suffering automatically produces control.

The evidence says otherwise. Psychological skills don’t emerge from pressure. They emerge from training under pressure, deliberately. We train grips. We train balance. We train timing.

The uncomfortable question is no longer whether mental training matters — but why a sport built on adaptation still treats the mind as something that should take care of itself.

What would change if your dojo trained the mind the same way it trains the body — not to win more matches, but to stop losing them before they begin?

Quiz: According to the research, what psychological factor consistently separates winning judoka from losing ones?

A) Number of years training

B) Higher self-confidence and lower anxiety

C) Body mass index

D) Preference for certain techniques

Answer

Correct Answer: B) Higher self-confidence and lower anxiety

Explanation: Research cited in the post shows that winners exhibit more self-confidence and lower levels of both cognitive and somatic anxiety than those who lose.

⸻

(1) Matsumoto, D., Konno, J. and Ha, H.Z. (2018) 'Sport Psychology in Combat Sports', in Kordi, R., Maffulli, N., Wroble, R.R. and Wallace, W.A. (eds.) Sports Medicine and Sciences of Combat Sports. Oxford, England: Bladon Medical Publishing. Available at: https://www.usjf.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Sport-Psychology-in-Combat-Sports.pdf (Accessed: 24 May 2024)

(2) Lonsdale, M. (2013) Mental Preparation & Sports Psychology for Judo A Primer. Available at: https://www.media.usja.net/2013/02/Mental-Preparation-2013.03ML.pdf (Accessed: 24 May 2024)

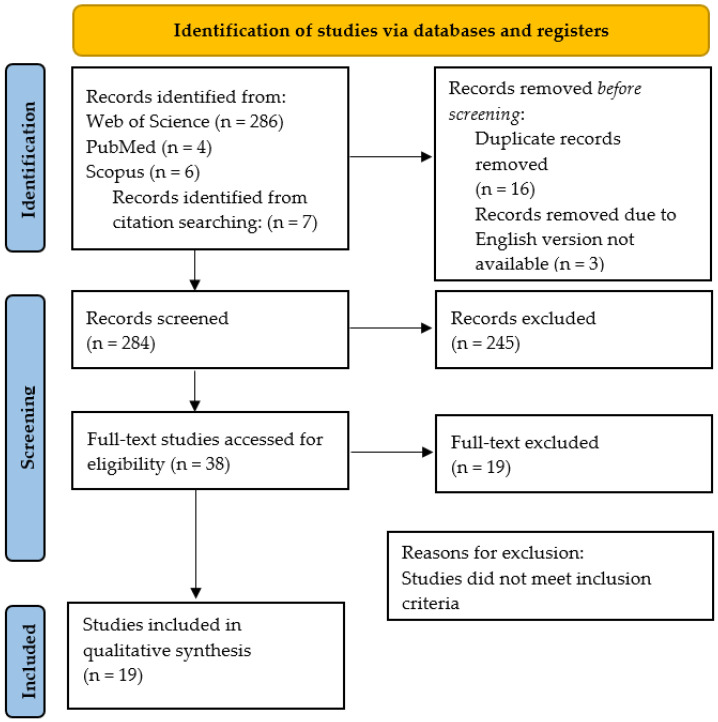

(3) Rossi, C., Roklicer, R., Tubic, T., Bianco, A., Gentile, A., Manojlovic, M., Maksimovic, N., Trivic, T. and Drid, P. (2022) 'The Role of Psychological Factors in Judo: A Systematic Review', International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), p. 2093. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19042093

Member discussion: