The first time Marcus blacked out mid-grip wasn’t from a choke—it was anxiety. National qualifiers. Elimination round. His fingers were wrapped tight around the judogi when his brain screamed run. He didn’t. He fell. Got up. Fought again.

Judo is more than throws and falls. It’s a mental crucible—quietly remaking you from the inside out.

Newer research suggests that judo doesn’t just make you stronger or more skilled. It might actually make you more you: more focused, more calm, more curious. This post explores how long-term judo practice influences personality, emotional intelligence, and even anxiety.

Spoiler: it’s good news for aging judoka.

On this NotebookLM episode, we explore the relationship between emotional intelligence, anxiety, and personality traits in combat sports athletes. The sources we look at specifically compare different combat sport types (grappling vs. striking) and athlete characteristics such as gender and skill level to understand their impact on anxiety and emotional intelligence.

⸻

Throwing Anxiety to the Mat

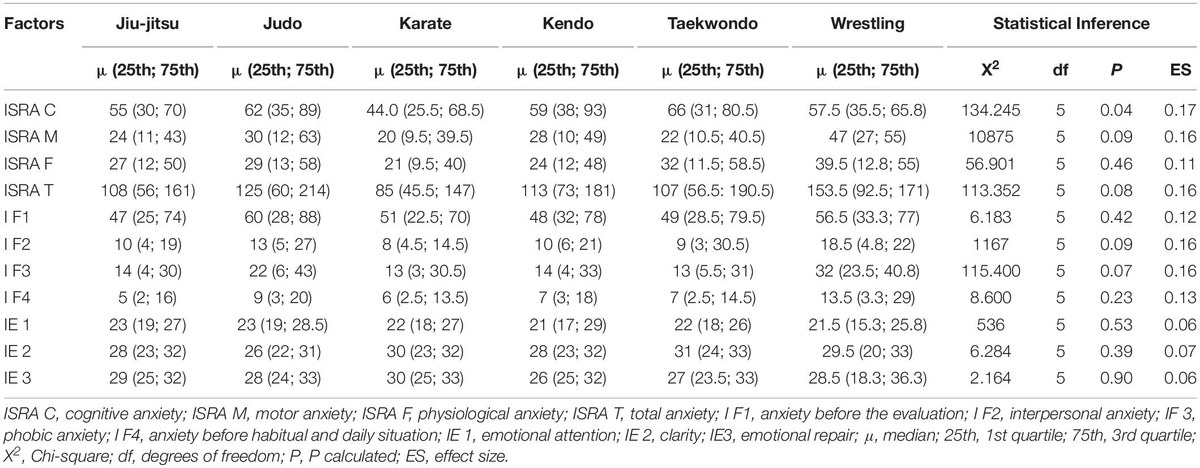

If you’ve ever felt nervous before randori—or avoided competition entirely—you’re not alone. Anxiety is rampant in combat sports, especially in grappling disciplines like judo. Studies show that judo athletes tend to experience higher levels of interpersonal and phobic anxiety, likely due to the intense close contact and psychological cat-and-mouse of grips and attacks.

One study notes that the moment before a throw—the “gripping time”—can spike anxiety because it leaves athletes hyper-aware of their opponent’s intentions. Ironically, this tension might be what trains judoka to better navigate high-stress situations.

Further Reading: Merino Fernández, María & Valenzuela Perez, Diego & Aedo-Muñoz, Esteban & Brabec, Lindsei & Brito, Ciro & Miarka, Bianca & López Díaz de Durana, Alfonso. (2023). Emotional intelligence and anxiety disorder probabilities in grappling and striking combat sport athletes: comparison with regression analysis. Ido Movement for Culture. 29. 65-70. 10.14589/ido.23.3.7.

So how do elite athletes deal with it? They develop emotional intelligence.

⸻

Emotional IQ: The Hidden Belt System

Researchers break emotional intelligence into three parts:

- Emotional attention: noticing how you feel

- Emotional clarity: understanding what those feelings mean

- Emotional repair: managing your emotions when they go haywire

High-level judoka consistently score better in clarity and repair, which helps them stay composed under pressure. In fact, elite athletes were found to have 40% less total anxiety than lower-level practitioners. The implication? Learning to control your emotions might be just as important as controlling your opponent’s balance.

Further Reading: Merino Fernández, María & Brito, Ciro & Miarka, Bianca & López Díaz de Durana, Alfonso. (2020). Anxiety and Emotional Intelligence: Comparisons Between Combat Sports, Gender and Levels Using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale and the Inventory of Situations and Anxiety Response. Frontiers in Psychology. 11. 130. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00130

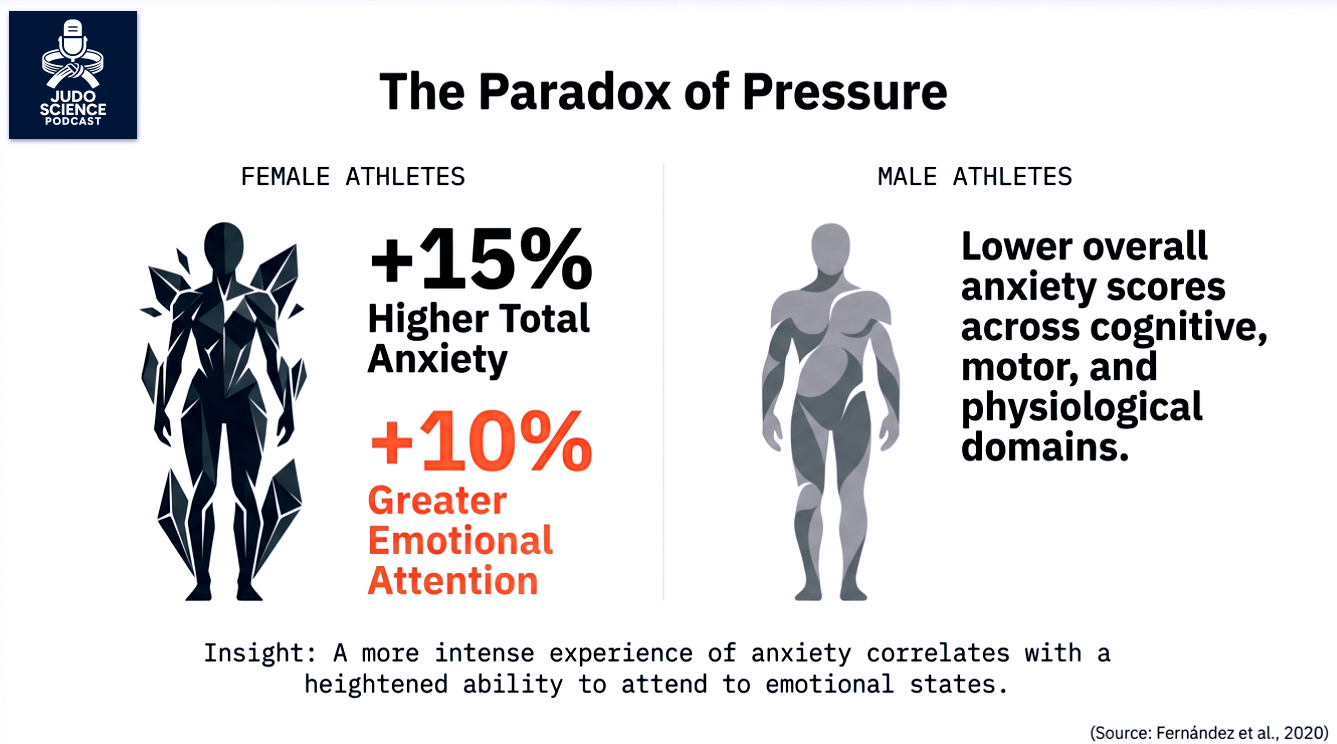

Interestingly, female athletes report more anxiety overall—but they also tend to have better emotional attention. It’s a reminder that emotional strength doesn’t mean the absence of anxiety. It means knowing it’s there and choosing your response.

⸻

Grappling with Personality

Ask Mari—a 63-year-old brown belt who’s been practicing for nearly two decades—if judo changed her. She won’t hesitate: “I used to panic if someone stood too close to me in line. Now I’m the one teaching breakfalls to college wrestlers.”

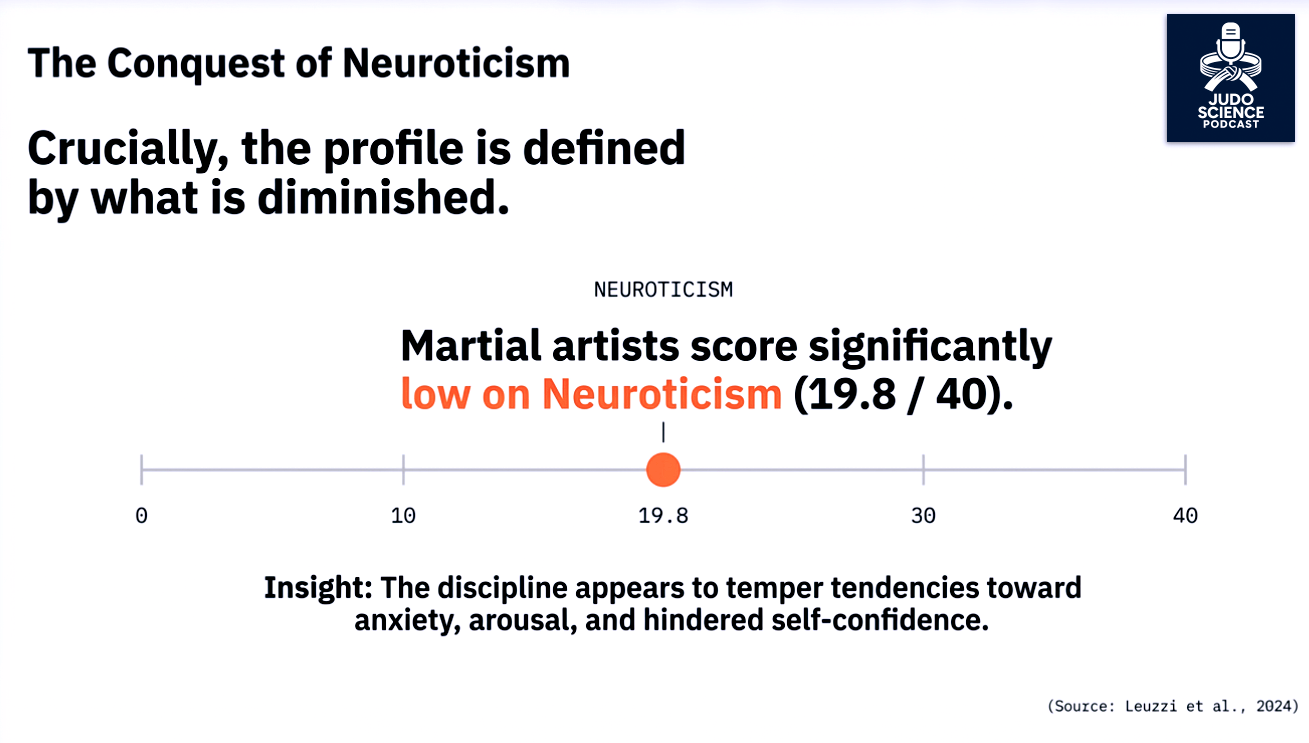

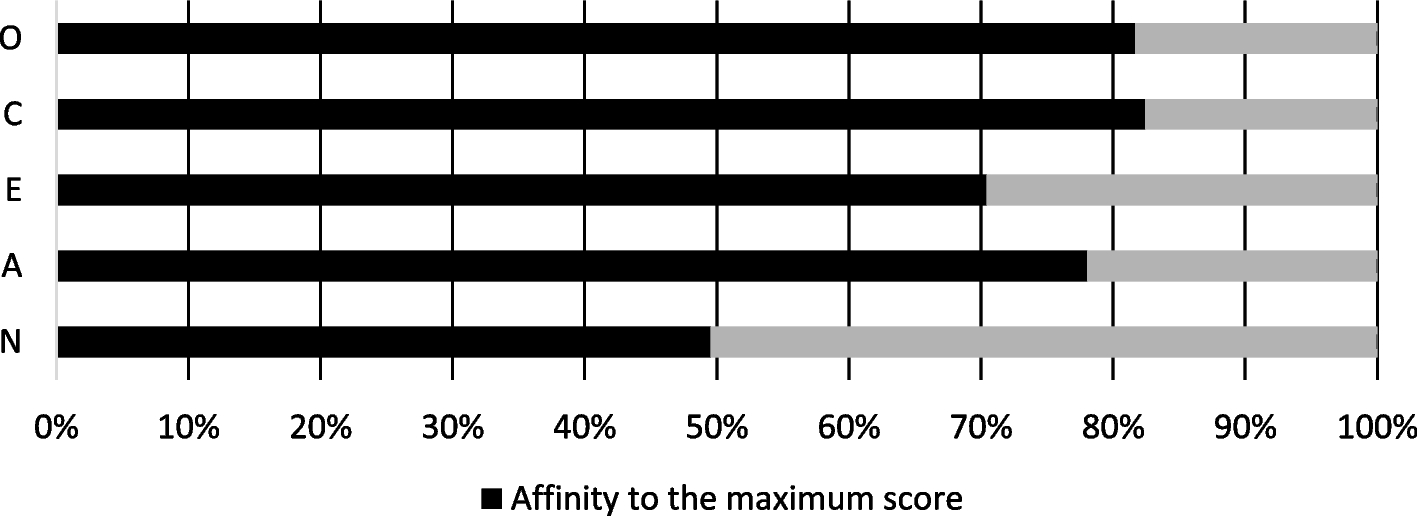

Science backs her up. A study of over 700 adult martial artists found long-time judoka score high in openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, and agreeableness. Neuroticism? Not so much. These weren’t born traits—they got stronger with years on the mat. Turns out, grappling teaches more than balance. It builds who you become.

Further Reading: Leuzzi, Gaia & Giardulli, Benedetto & Pierantozzi, Emanuela & Recenti, Filippo & Brugnolo, Andrea & Testa, Marco. (2024). Personality traits and levels of anxiety and depression among martial artists: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychology. 12. 607. 10.1186/s40359-024-02096-8

As a reminder, here are the four out of five major personality traits that judoka scored high on:

- Openness: curiosity and appreciation for new experiences

- Conscientiousness: discipline and reliability

- Extraversion: social confidence

- Agreeableness: trust and empathy

They also scored low in neuroticism, the trait most associated with anxiety and emotional instability. And here’s the kicker: these traits were even stronger in practitioners with decades of experience.

What does this mean? Judo might not just select for certain personality types—it could be cultivating them.

⸻

When the Mat Becomes a Mirror

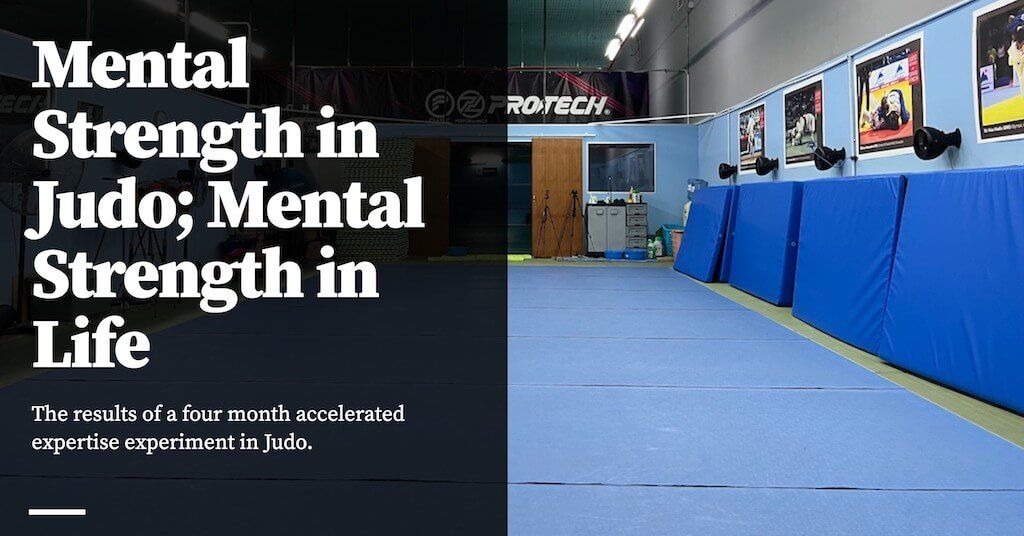

This theme is beautifully explored in the essay “Mental Strength in Judo, Mental Strength in Life” by Cedric Chin. In it, he describes how judo became a kind of psychological mirror—a space where he couldn’t hide from his instincts under pressure. His reactions during randori weren’t just athletic; they were revealing.

“Judo has a way of showing you who you are—especially when things go wrong.”

The piece underscores what research now confirms: judo doesn’t just train movement. It trains awareness—of fear, control, overreaction, and the ability to respond with intent instead of impulse. For many, this reflection process becomes the real value of practice.

⸻

Beyond Technique: Training for the Mind

Why does judo have this effect?

Theories include:

- The cooperative nature of uchikomi and randori

- The need to manage fear and aggression in close contact

- The philosophical elements (kata, bowing, dojo etiquette) that promote reflection and humility

These components combine into a “training container” that naturally fosters emotional growth. And for those starting later in life, this might be even more powerful. Long-time practitioners reported lower levels of depression and anxiety compared to national averages for their age group.

⸻

Takeaways for the Tatami

- Judo trains more than the body—it conditions the mind.

- Higher-level judoka show better emotional regulation and less anxiety.

- Grappling sports produce unique psychological stressors that can become strengths.

- Female athletes face higher anxiety but may have superior emotional awareness.

- Personality traits like openness and conscientiousness are elevated in long-term martial artists.

- The longer you practice, the stronger your psychological resilience becomes.

⸻

Final Thought

The most underrated judo skill isn’t ukemi—it’s adaptation. Falling well, sure. But also the ability to pivot, breathe, re-center. To be gripped by fear and still commit to the throw.

Every practice is a rehearsal for reality: messy, close-contact, unpredictable. And the version of you that walks off the mat? That’s the one learning to fall better—at life.

Quiz: According to the research, what distinguishes high-level judo athletes in terms of emotional intelligence and anxiety?

A) They experience more anxiety but manage it with superior fitness

B) They show no difference in anxiety or emotional intelligence

C) They exhibit lower anxiety and higher emotional clarity and repair

D) They rely more on physical preparation than emotional regulation

Answer

Correct Answer: C) They exhibit lower anxiety and higher emotional clarity and repair

Explanation: High-level judoka were shown to have ~40% less total anxiety and ~10% better emotional clarity and repair compared to lower-level athletes, suggesting emotional intelligence plays a key role in elite performance

⸻

(1) Leuzzi, Gaia & Giardulli, Benedetto & Pierantozzi, Emanuela & Recenti, Filippo & Brugnolo, Andrea & Testa, Marco. (2024). Personality traits and levels of anxiety and depression among martial artists: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychology. 12. 607. 10.1186/s40359-024-02096-8.

(2) Merino Fernández, María & Brito, Ciro & Miarka, Bianca & López Díaz de Durana, Alfonso. (2020). Anxiety and Emotional Intelligence: Comparisons Between Combat Sports, Gender and Levels Using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale and the Inventory of Situations and Anxiety Response. Frontiers in Psychology. 11. 130. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00130.

(3) Merino Fernández, María & Valenzuela Perez, Diego & Aedo-Muñoz, Esteban & Brabec, Lindsei & Brito, Ciro & Miarka, Bianca & López Díaz de Durana, Alfonso. (2023). Emotional intelligence and anxiety disorder probabilities in grappling and striking combat sport athletes: comparison with regression analysis. Ido Movement for Culture. 29. 65-70. 10.14589/ido.23.3.7.

Member discussion: