The throw feels right — until it doesn’t.

You step in for Osoto Gari. The grip is secure. The timing feels close enough. You commit. And instead of impact, there’s resistance. Weight that refuses to move. A leg that stubbornly remains. You land half-turned, slightly embarrassed, wondering why the same throw looked devastating when they did it.

From the outside, the difference looks like confidence. Or aggression. Or experience. From the inside, it’s physics.

Biomechanics doesn’t care how long you’ve trained, how hard you pull, or how much fighting spirit you summon. It only cares whether forces line up, whether momentum is generated at the right moment, and whether your body behaves like a coordinated system — or a collection of parts working against each other.

That is where modern biomechanics quietly parts ways with how most of us were taught judo.

This recap pulls together what recent research reveals about kuzushi, action invariants, and three familiar throws — Harai Goshi, Uchimata, and Osoto Gari. Not to replace tradition, but to expose where tradition explains what to do, while science explains why it actually works.

And sometimes, those explanations are uncomfortably different.

In this NotebookLM podcast, we explore the biomechanics and strategic applications of various judo throws. They break down complex techniques like Harai Goshi, Uchimata, and Osoto Gari, explaining the underlying physics such as force application, angular momentum, and the critical role of unbalancing (kuzushi).

⸻

Kuzushi: Unbalancing Is Not What You Think

“No kuzushi, no throw” is one of judo’s most repeated truths. It’s also one of its most misleading. Biomechanics doesn’t reject kuzushi — it reframes it.

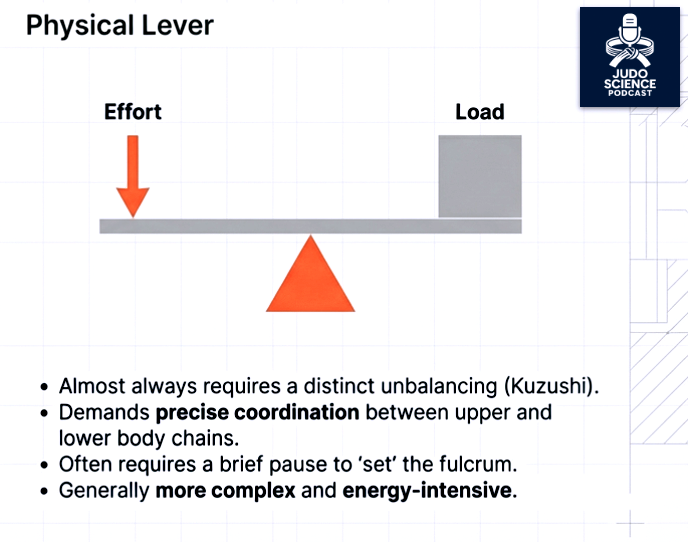

In physical lever techniques such as Seoi Nage, unbalancing is non-negotiable. Without a clearly displaced centre of mass, there is no stable fulcrum. The system never loads. The throw fails before it begins.

But couple techniques, like Osoto Gari, operate under different rules. Here, success can emerge from two opposing forces applied simultaneously: one force driving uke backward, the other removing their base of support. If uke is already moving, stiff, or poorly aligned, kuzushi may never appear as a distinct, teachable phase. It happens inside the motion, compressed and efficient — almost invisible.

Watch elite competitors closely and you’ll miss it if you’re waiting for a dramatic pull. The unbalancing is there, but it’s economical, transient, and inseparable from the throw itself. This is the first quiet heresy biomechanics introduces:

Some throws work not because kuzushi is exaggerated, but because it never announces itself.

For judokas raised on static uchikomi and clearly separated phases, this should feel unsettling. It suggests that effort isn’t the missing ingredient. Timing, force direction, and system coordination are.

Kuzushi isn’t a ritual. It’s a tactical choice.

Even in couple techniques, a brief pause or moment of stillness can make or break the setup. Effective kuzushi isn’t optional—it’s a tactical choice. For a deeper dive into the fundamental role of kuzushi, check out this excellent resource from JudoInfo.

⸻

Action Invariants: The Hidden Architecture of Throws

If kuzushi is when a throw becomes possible, action invariants explain how it reliably happens.

Biomechanics research identifies recurring movement patterns — stable solutions the body returns to again and again under pressure. These are not stylistic preferences. They’re mechanical necessities.

- General action invariants describe how the body closes distance: straight entry, partial rotation (0–90°), or full rotation (up to 180°).

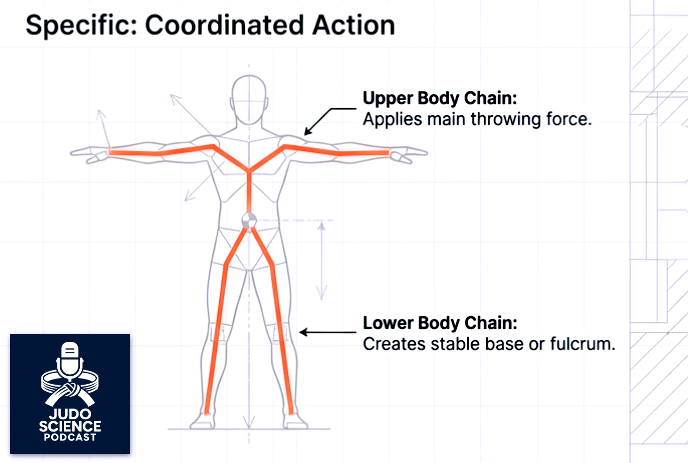

- Specific action invariants describe how arms, torso, hips, and legs coordinate to transmit force through the system.

This is why elite judokas appear consistent rather than creative. They aren’t improvising under stress; they’re executing well-grooved solutions that minimise degrees of freedom and maximise efficiency.

When Teddy Riner makes a throw look effortless, it’s not because he’s relaxed. It’s because the system is stable. Every segment contributes at the right time, in the right direction, without internal conflict.

Most training failures aren’t motivational. They’re architectural.

⸻

Harai Goshi: The Hip Leads, the Leg Assists

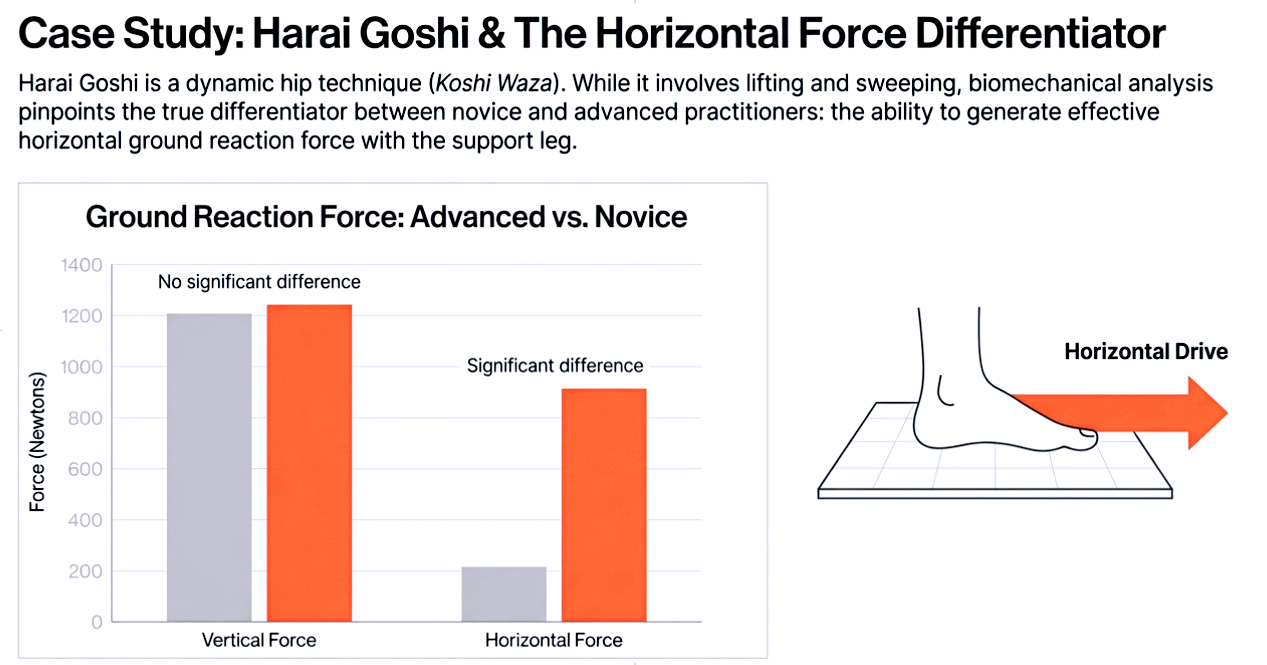

Harai Goshi is often taught as a dramatic sweeping action. Biomechanics tells a different story.

High-level execution depends less on vertical lift and more on horizontal force generation through the support leg. Skilled judokas drive sideways, rotating the hips powerfully while maintaining close torso contact. Without that contact, energy leaks and the throw collapses.

Key findings are consistent across studies:

- Close torso-to-torso contact is non-negotiable for effective force transfer.

- The hip initiates the movement; the sweeping leg follows.

- Horizontal drive matters more than vertical lift.

Further Reading: Pucsok, Jozsef & Nelson, K & Ng, E. (2001). A kinetic and kinematic analysis of the Harai-goshi judo technique. Acta physiologica Hungarica. 88. 271-80. 10.1556/APhysiol.88.2001.3-4.9.

Think of the hip not as a lifting mechanism, but as a rotating arm in a mechanical system. Without timing and contact, the sweep becomes decorative rather than functional.

This is why advanced Harai Goshi feels compact and decisive, while novice versions feel wide, slow, and strangely exhausting. They’re pushing in the wrong direction.

⸻

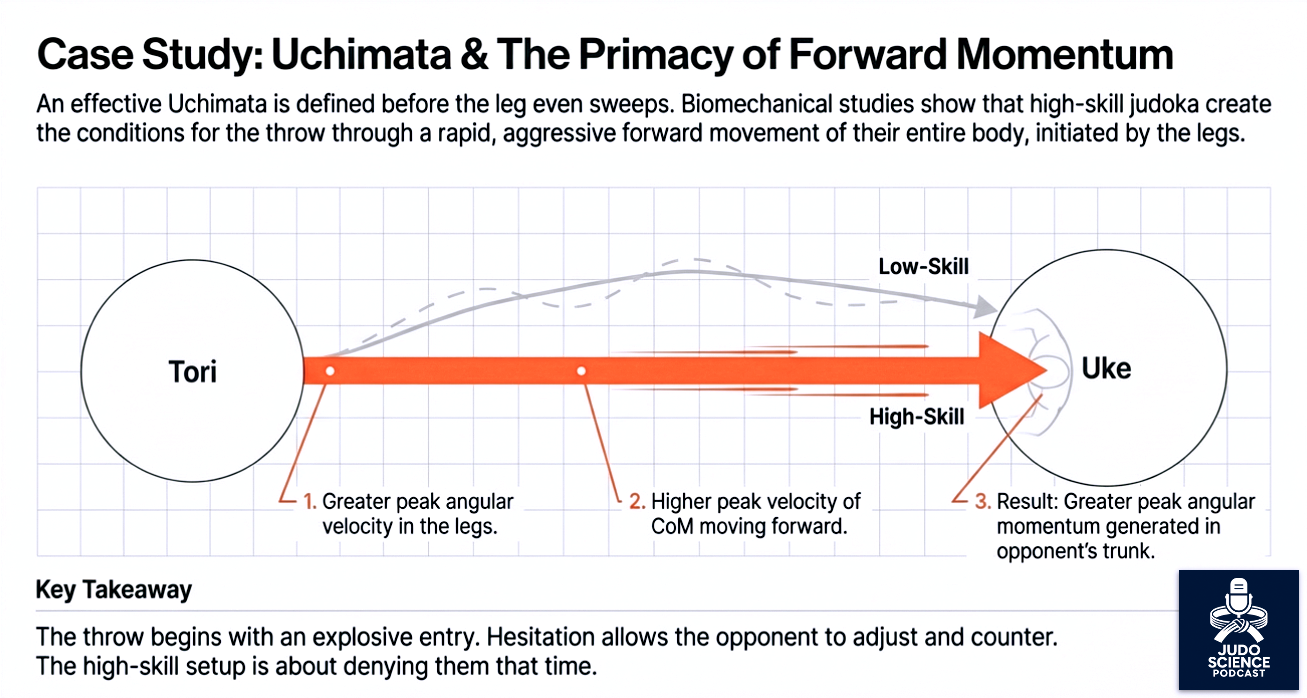

Uchimata: Winning Before the Rotation Begins

Uchimata is often described as elegant. Biomechanics reveals that it’s brutally aggressive — just not in the way most people think.

Successful Uchimata is defined by explosive forward drive of the centre of mass, not graceful leg elevation. High-level athletes close distance rapidly, generating angular momentum in uke’s trunk before the leg ever dominates the picture.Research shows:

- Higher peak forward velocity correlates with successful execution.

- Trunk instability precedes visible rotation.

- Defensive postures limit knee extension, reducing effectiveness.

Uchimata works best when uke is upright and vulnerable — not because they’re balanced, but because their structure allows the thrower to fully express forward force.

Ever seen Uchimata compared side-by-side with Harai Goshi? Watch this excellent video demonstration that highlights the subtle yet important biomechanical differences between these throws.

⸻

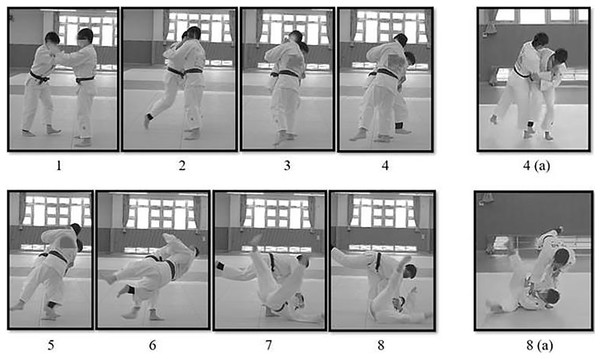

Osoto Gari: Where the Head Leads, the Body Follows

Osoto Gari looks simple. Biomechanically, it’s anything but. Motion-capture studies reveal that head movement plays a critical role in generating sweep velocity. Forward head tilt improves visual processing, initiates trunk rotation, and sets up a rapid jack-knife effect through the body.

The sequence matters:

- Head movement leads.

- Trunk accelerates.

- The sweeping leg follows with increased velocity.

Further Reading: Liu L, Deguchi T, Shiokawa M, Hamaguchi K, Shinya M. Analysing head and trunk motion in the judo osoto-gari technique: relationship to sweeping-leg velocity. PeerJ. 2025 Jan 23;13:e18862. doi: 10.7717/peerj.18862. PMID: 39866562; PMCID: PMC11766671.

Bent-knee variations generate greater force, though timing remains consistent across styles. What separates competition-speed Osoto from demonstration versions is not technique selection, but temporal compression — explosive kuzushi, minimal telegraphing, and decisive follow-through.

Watch elite competition footage and you’ll see it everywhere: head-whipping, trunk-crunching Osoto Gari that looks violent precisely because it is efficient.

The head doesn’t just look where the throw goes. It tells the system when to fire.

Takeways for the Tatami

The uncomfortable implication of biomechanics is this:

Most judokas are not failing because they lack effort.

They’re failing because they’re training the wrong variables.

Static uchikomi builds familiarity, not adaptability. Without movement, timing, and force variability, the system never learns to stabilise under pressure.

Effective training must include:

- Dynamic unbalancing, not posed entries

- Movement-based drills that stress coordination

- Repetition of patterns, not poses

Throws don’t fail because the athlete didn’t try hard enough. They fail because the system never learned to behave as a system.

⸻

Final Thought

Biomechanics doesn’t strip judo of its soul. It strips away its myths.

If you trained like a physicist — testing variables, observing outcomes, refining systems — what would you stop doing immediately?

And what might finally start working?

Quiz: According to the blog post, what role does head movement play in executing a powerful Osoto Gari?

A) It mainly serves to distract the opponent

B) It increases leg sweep speed by initiating trunk rotation

C) It stabilizes the thrower’s balance without affecting speed

D) It has no significant impact on the throw

Answer

Correct Answer: B) It increases leg sweep speed by initiating trunk rotation

Explanation: Tilting the head forward improves leg sweep speed by coordinating with the trunk, creating a jack-knife effect that boosts angular momentum.

⸻

(1) Kim, Sung-Sup & Kim, Eui-Hwan & Kim, Tae-Whan. (2007). A Biomechanical Analysis of Judo`s Kuzushi(balance-breaking) Motion. Korean Journal of Sport Biomechanics. 17. 207-216. 10.5103/KJSB.2007.17.2.207.

(2) Sacripanti, Attilio. (2012). A Biomechanical Reassessment of the Scientific Foundations of Jigoro Kano's Kodokan Judo.

(3) Helm, Norman & Prieske, Olaf & Muehlbauer, Thomas & Krüger, Tom & Chaabene, Helmi & Granacher, Urs. (2018). Validation of A New Judo-Specific Ergometer System in Male Elite and Sub-Elite Athletes. Journal of sports science & medicine. 17. 465-474.

(4) Sogabe, Akitoshi & Sasaki, Taketo & Sakamoto, Michito & Ishikawa, Yoshihisa & Hirokawa, Mitsushi & Kubota, Hiroshi & Yamasaki, Shunsuke. (2008). Analysis of patterns of response to kuzushi in eight drections based on plantar pressure and reaction movement. Archives of Budo. 4. 70-77.

(5) Pucsok, Jozsef & Nelson, K & Ng, E. (2001). A kinetic and kinematic analysis of the Harai-goshi judo technique. Acta physiologica Hungarica. 88. 271-80. 10.1556/APhysiol.88.2001.3-4.9.

(6) Groom, D. (2024) Harai Goshi, Judo Way Of Life. Available at: https://www.thejudowayoflife.com/harai-goshi (Accessed: 23 March 2025).

(7) Katagiri-Adamcik, R. (2023) Harai-Goshi Tips | Riki Judo Dojo, YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1qdr_NEP0wM (Accessed: 24 March 2025).

(8) Kim, Eui-Hwan & Cho, Dong-Hee & Kwon, Moon-Seok. (2002). A Kinematic Analysis of Uchi-mata(inner thigh reaping throw) by Kumi-kata types in Judo. Korean Journal of Sport Biomechanics. 12. 63-87. 10.5103/KJSB.2002.12.1.063.

(9) Hamaguchi, Kazuto & Furukawa, Takumi & Takeuchi, Sora & Sasakawa, Yoshiki & Deguchi, Tatsuya. (2024). BIOMECHANICAL ANALYSIS OF JUDOKAS`THROWING TECHNIQUES: FOCUS ON THE PREPARATION PHASE..

(10) Yoon, Hyun. (2005). The Kinetic Analysis of the Lower Extremity Joints when Performing Uchi-mata by Uke`s Posture in Judo. Korean Journal of Sport Biomechanics. 15. 167-183. 10.5103/KJSB.2005.15.2.167.

(11) Gomes, Fábio & Meira Jr, Cassio & Franchini, Emerson & Tani, Go. (2003). Specificity of Practice in Acquisition of the Technique of O-Soto-Gari in Judo. Perceptual and motor skills. 95. 1248-50. 10.2466/PMS.95.8.1248-1250.

(12) Gomes, Fábio & Bastos, Flavio & Meira Jr, Cassio & Neiva, Jaqueline & Tani, Go. (2016). Effects of distinct practice conditions on the learning of the o soto gari throwing technique of judo. Journal of Sports Sciences. 35. 10.1080/02640414.2016.1180418.

(13) Liu L, Deguchi T, Shiokawa M, Hamaguchi K, Shinya M. Analysing head and trunk motion in the judo osoto-gari technique: relationship to sweeping-leg velocity. PeerJ. 2025 Jan 23;13:e18862. doi: 10.7717/peerj.18862. PMID: 39866562; PMCID: PMC11766671.

(14) Imamura, R., Iteya, M. and Takeuchi, Y. (2005) The Biomechanics of Osoto-gari, Association for the Scientific Studies on Judo. Available at: http://150.60.32.66/en/docs/kiyou7imamura47.pdf (Accessed: 23 March 2025).

(15) Kuo, K. (2001). COMPARISON BETWEEN KNEE-FLEXED AND KNEE-EXTENDED STYLES IN THE MAJOR OUTER LEG SWEEP. 19 International Symposium on Biomechanics in Sports (2001) .

(16) Jagić, Marija & Hraski, Željko & Mejovšek, Mladen. (2005). Comparative kinematic analysis of teaching and competitive performance of the Osoto-Gari throw.

(17) Liu, L. (2020). Measuring and Analyzing the Angular Momentum Produced in the Application of the Judo Throwing Technique Osoto-Gari. 38th International Society of Biomechanics in Sport Conference.

(18) Sacripanti, Attilio. (2019). The increasing importance of Ashi Waza, in high level competition. (Their Biomechanics, and small changes in the form). 10.48550/arXiv.1907.01220.

(19) Simenko, J 2023, THE SYMMETRY OF BILATERAL ASHI-WAZA THROWS EXECUTION IN YOUTH U-14 CATEGORY JUDOKAS. in H Sertić, S Čorak & I Segedi (eds), Proceedings book 7th European Judo Research And Science Symposium & 6th Scientific And Professional Conference On Judo: “Applicable research in judo“. Faculty of Kinesiology, University of Zagreb, Croatia, Zagreb, pp. 39-42, 7th European Judo Research And Science Symposium & 6th Scientific And Professional Conference On Judo: “Applicable research in judo“, Poreč, Croatia, 19/06/23.

Member discussion: