Are Foot Sweeps the Future of Judo?

At the 2016 Rio Olympics, Lukas Krpalek scored gold with what looked like a whisper: a foot sweep so understated the crowd barely reacted—until the replay showed his opponent airborne. Welcome to judo’s silent coup.

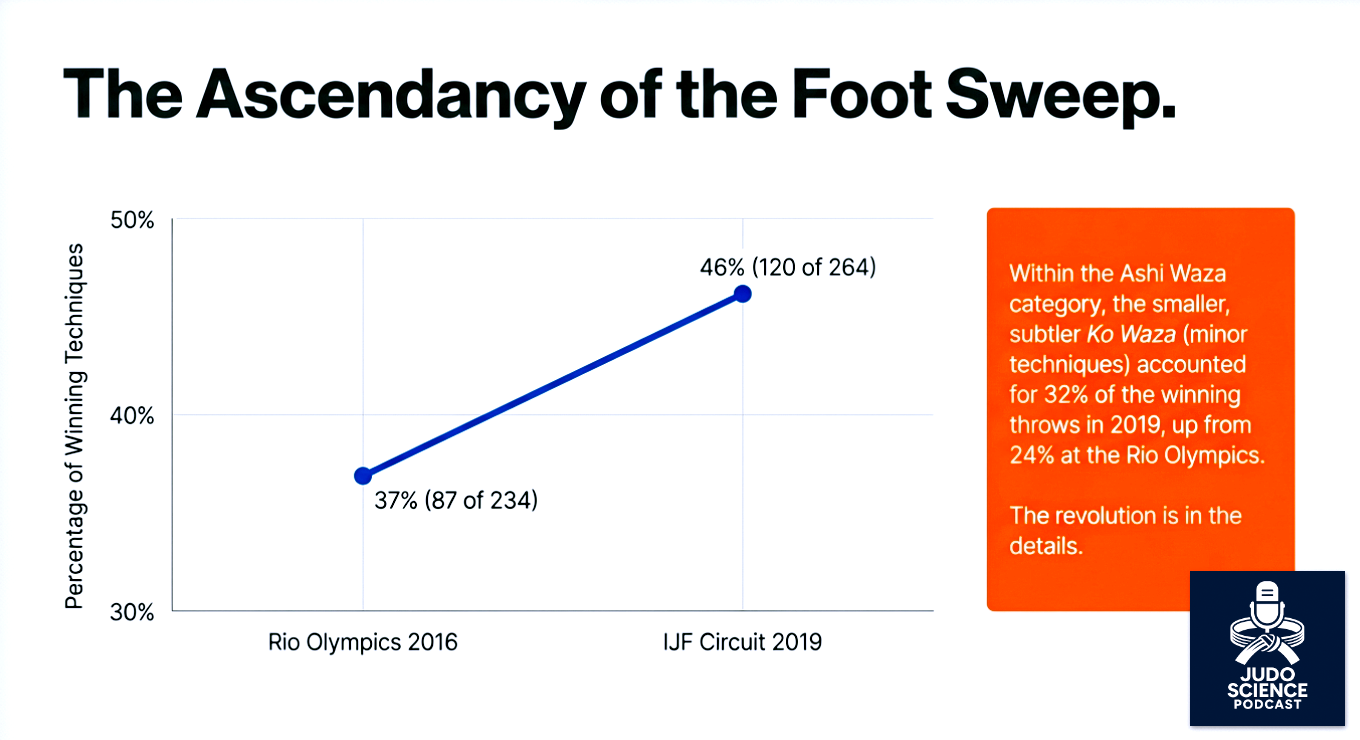

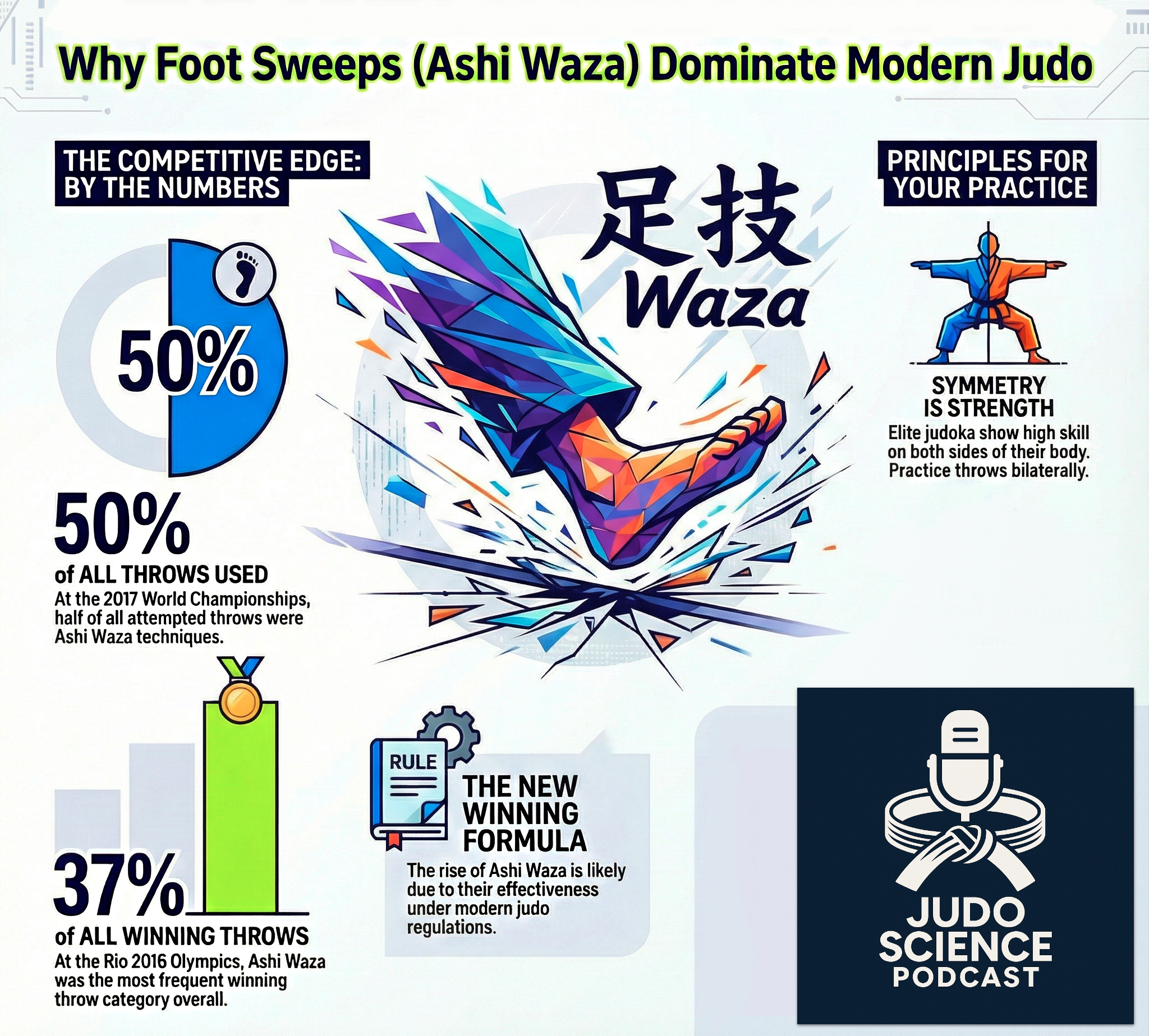

In an era where throws like Uchi Mata and Seoi Nage have long held center stage, a quiet revolution is taking place underfoot. At the 2016 Rio Olympics and the 2017 World Championships, foot techniques (Ashi Waza) accounted for nearly half of all successful throws. Subtle and swift, these leg-based techniques are claiming a growing share of victories in high-level judo.

But why are these “minor” techniques suddenly turning major? The answer lies in a mix of changing rules, biomechanics, and strategic evolution.

In this NotebookLM podcast, we take a look at Ashi-Waza (foot sweep) techniques in Judo, exploring both practical application and scientific analysis.

⸻

Footnotes Of Power

Most of the so-called Ko-Waza — Ko Uchi Gari, Ko Soto Gari, Ko Uchi Barai, and their kin — follow the same underlying biomechanical principle: use the foot to hook, sweep, or reap the opponent’s foot while the arms create an opposing force. Think of it as operating a physical pendulum that slams into Uke’s base. Depending on friction, it might glide like a broom (Barai) or dig in like a crowbar (Gari, Gake).

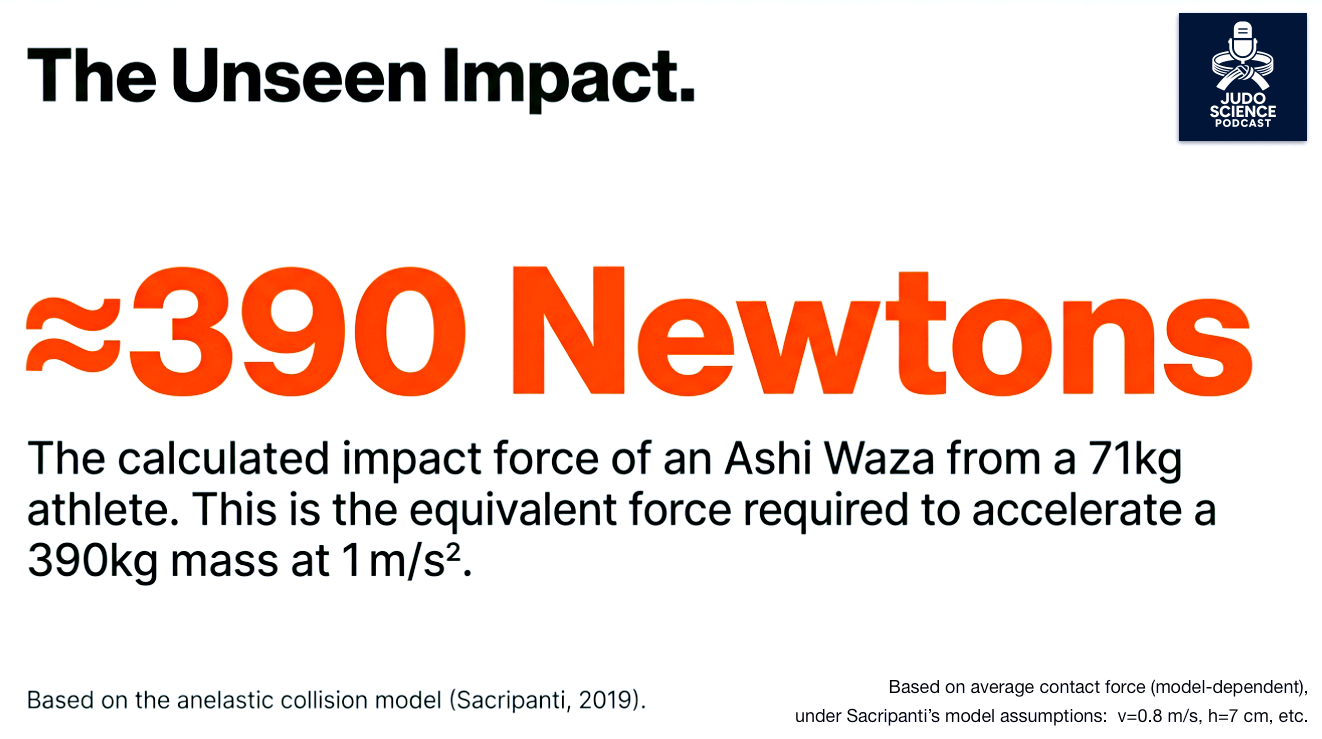

These throws don’t shout. They whisper — and then the opponent hits the floor. The physics backs it up:

- Low friction? A Barai (sweep) is enough.

- High friction? Gari or Gake (reap/hook) requires more force.

In fact, a 71kg judoka can generate nearly 390 Newtons of force in these small movements—that’s enough to destabilize someone five times their weight if applied at the right moment.

⸻

To see a vivid explanation of these principles in action, check out this excellent breakdown by Travis Stevens on how to set up your basic foot sweep techniques.

⸻

Technique Evolves Like Language

Competitive judo has quietly evolved beyond the strict lines of traditional Kodokan forms. While the essence of the technique remains biomechanically consistent, elite judokas have adapted foot sweeps to fit their body types and tactics:

- Ko Soto Gari? Nakamura Yukimasa swaps foot for thigh.

- Ko Uchi Gari? Fukumi Tomoko shows a refined, classical application with elite timing.

- Chin pin strategy? Tying down your opponent’s arm with your chin and then launching a sweep? That’s tactical innovation.

These aren’t rogue improvisations. They’re intelligent adaptations that exploit the same biomechanical truths with tactical nuance.

For a deeper dive into the value of these techniques in modern judo, read this insightful blog post on The Merits of Ashi-Waza.

⸻

Kids Do It Symmetrically (For Now)

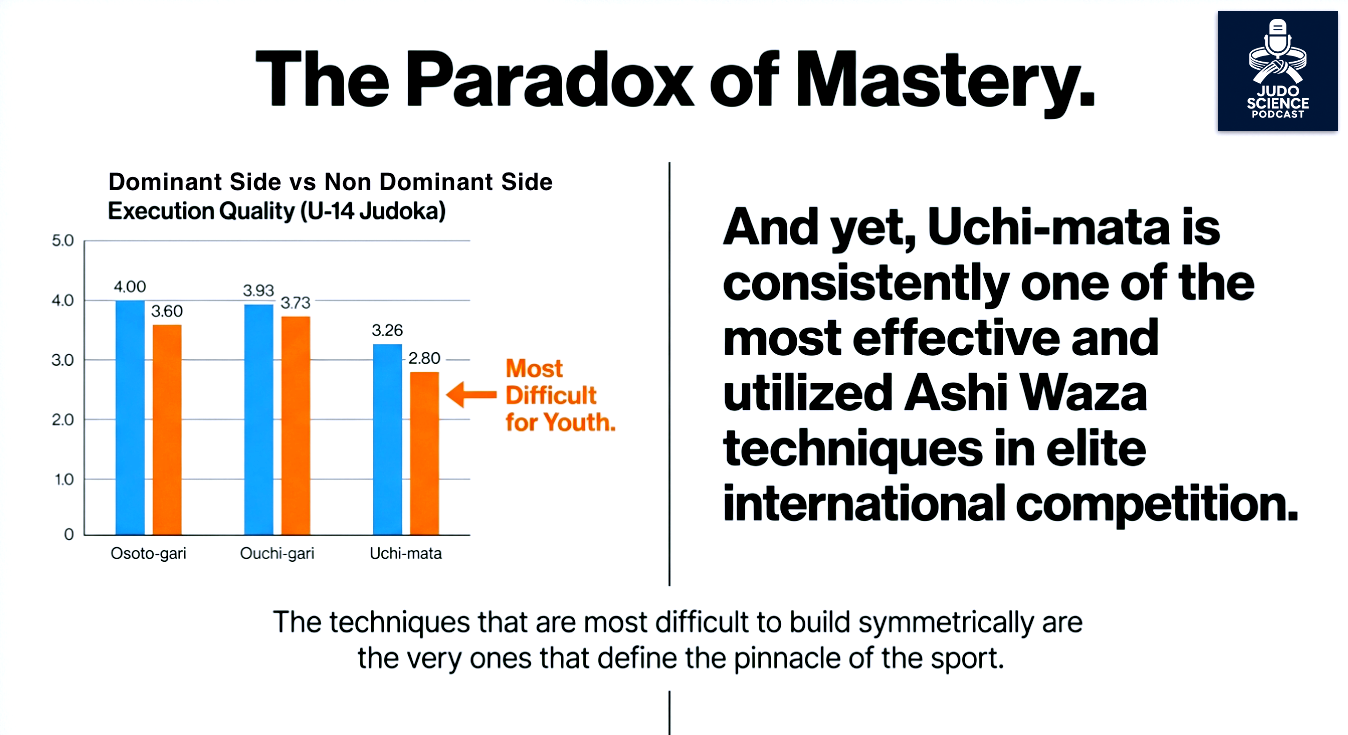

Interestingly, studies on U-14 judokas show that Ashi Waza are performed with surprising symmetry between dominant and non-dominant sides. Throws like O Soto Gari and Ko Uchi Gari scored well on both sides, likely due to being introduced early in training.

But Uchi Mata? Not so much. This demanding throw showed poorer performance, likely because it’s taught later and requires more motor control.

And here’s the catch: around age 14-16, as specialisation intensifies, asymmetries start to emerge. The risk? Over-reliance on one side could limit technical diversity and strategic options.

To visualize how young athletes can develop effective foot sweeps early, this Uchi Mata and Ko Uchi Gari drill is a great teaching tool.

⸻

The Traditionalist’s Tension

Not everyone’s cheering. Some Kodokan purists argue that Ashi Waza overemphasis flattens the spirit of judo, reducing the art to mechanical foot tags. “It’s beautiful, yes,” says retired coach Hiroshi Kameda, “but where’s the risk? Where’s the fight?”

It’s a debate as old as martial arts: elegance versus aggression.

⸻

Takeaways for the Tatami

- Foot techniques are winning more fights: Ashi Waza accounted for up to 50% of winning throws in recent international events.

- All Ko-Waza share one engine: Whether it’s a hook, reap, or sweep, the underlying force system remains the same.

- Friction decides your weapon: Sweep when light, reap when grounded.

- Variation is not violation: Modern tweaks still honor biomechanical fundamentals.

- Train both sides early: Bilateral skill pays off long-term, especially before asymmetries set in.

⸻

Final Thought

In the grand orchestra of judo, Ashi Waza used to be the quiet section. But now, these subtle footnotes are leading the symphony.

Are you paying enough attention to what’s happening below the belt?

Quiz: According to the biomechanical research, what common physical principle underlies various Ashi‑Waza techniques like Ko‑Uchi Gari, Ko‑Soto Gari, and others?

A) Use of leverage through hip rotation

B) Application of a pendulum‑like leg sweep

C) Dependence on upper‐body pulling force

D) Static weight distribution

Answer

Correct Answer: B) Application of a pendulum‑like leg sweep

Explanation: The content above describes that these techniques share a pendulum‑style leg movement, colliding with uke’s foot, with variations (sweep, reap, hook) governed by friction and technique naming

⸻

(1) Sacripanti, Attilio. (2019). The increasing importance of Ashi Waza, in high level competition. (Their Biomechanics, and small changes in the form). 10.48550/arXiv.1907.01220.

(2) Simenko, J 2023, THE SYMMETRY OF BILATERAL ASHI-WAZA THROWS EXECUTION IN YOUTH U-14 CATEGORY JUDOKAS. in H Sertić, S Čorak & I Segedi (eds), Proceedings book 7th European Judo Research And Science Symposium & 6th Scientific And Professional Conference On Judo: “Applicable research in judo“. Faculty of Kinesiology, University of Zagreb, Croatia, Zagreb, pp. 39-42, 7th European Judo Research And Science Symposium & 6th Scientific And Professional Conference On Judo: “Applicable research in judo“, Poreč, Croatia, 19/06/23.

Member discussion: